The 2019 Chatham Translation Workshop

Geordie Kenyon Sinclair, Harvard University

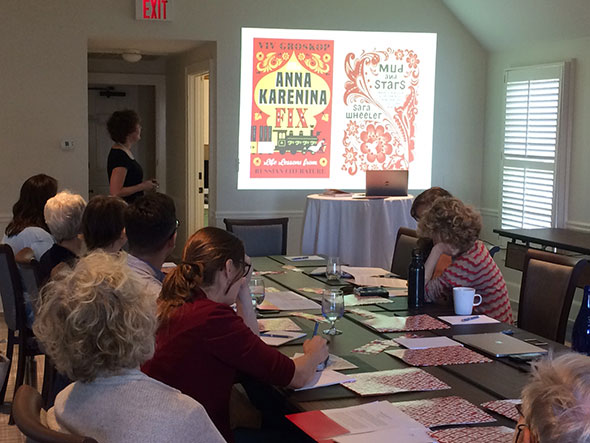

In September 2019 Read Russia brought together a group of innovative translators and publishers of Russian literature for three days of discussion in Chatham, Cape Cod. The Chatham Translation Symposium featured conversations about the state of the profession, and workshops on the craft of translation, but also discussions about how to raise the profile of Russian literature in English translation, and also how Read Russia might help with fresh initiatives in that direction.

I. Notes from 2019

Symposium participants suggested that promoting Russian literature translated into English would be well served by an organization that could emulate the activities of existing organizations that promote national literatures in the Anglophone world – among them sophisticated and more permanent German, French, and South Korean government initiatives. Though some of Read Russia’s functions already resemble the activities of these much older, established organizations, translators and publishers of Russian literature suggested in Chatham that Read Russia could more actively position itself as the leading (and more permanent) organization for the promotion of Russian literature and culture, “in the way that, for example, the Goethe Institute has become for Germanophone literature and culture.” Many symposium participants also emphasized how closer partnerships with other cultural institutions active in opera, theatre, music, and visual arts could be valuable in promoting Russian literature to audiences who enjoy Russian art and culture and yet whose ideas of Russian literature may have been on pause since reading Chekhov as undergraduates.

Symposium participants suggested Read Russia publish with greater transparency how the organization is funded, as well as statements about its aesthetic and political independence – especially as lay observers in the West have increasingly politicized responses to the public image of the Russian Federation. Part of this process could include new consideration of Read Russia’s visual brand identity, which plays heavily with Soviet colors (especially red), Cyrillic block capitals, and slogans that play on the living memory of the Soviet Union – even if several participants appreciated this playful use of visual vocabulary.

Most suggestions for how Read Russia should expand its support of Russian books in English revolved around post-publication publicity, although the group also discussed the importance of literary scouting. On that front, participants proposed that Read Russia could employ a scout to keep tabs on developments in the Russian literary scene, that literary popularity in Russia can reliably indicate what will be successful in English, and also that it could be useful to monitor translations being published in French, German, and other major book markets, to take note of successful publications not already being translated into English. The group was equivocal on whether the Anglophone book market is “missing out” on translating major works that could succeed in English, although translators and publishers clearly agree about the importance of constantly re-evaluating their choices of titles and projects, from perspectives as broad as possible. One area to consider might be “Russian-adjacent” literatures: works written partly in Russian, or in another language of the territory of the Russian Federation (or ex-USSR?), or work written in Russian outside of Russia. Another area is nonfiction – from literary nonfiction such as memoirs and biographies to even broader Russian cultural and historical works.

Symposium participants gathered in Chatham discussed the vital question of what makes and keeps their work relevant in the context of the Anglophone book market. While substantial novels are classically the product that one expects from translators of Russian literature, and while such publications (and their sales) may remain dominant as a metric of our “success,” the importance of shorter forms (including excerpts) and reaching readers through literary periodicals was raised. How to build such relationships with journals and magazines throughout the Anglophone world would be a good topic to discuss further, since translators often are unused to the hands-on role of being an author’s “editor and collaborator” as sometimes is required by periodical publishing.

To increase support for translations after publication, many participants endorsed the idea of Read Russia employing one or more literary publicists who would promote translations into English irrespective of publisher – a position that could even be funded jointly with the publishers in question. It was recommended that this should be “someone with expertise in promotion, PR, and publicity, who could conceive and implement ways to increase visibility for Russian literature in the media.” Publicists for Russian literature in English could arrange appearances at literary festivals, commissions for occasional pieces in the media, discussions on the radio and TV, and promotions in online media. They could also usefully find creative ways to generate more exposure, such as tie-ins with art exhibitions and the performing arts as well as commemorative events and anniversaries. Some symposium participants felt that publishers have moved away from their traditional role of “building” an author, or that changes in the book market have made this more difficult: this proposed role could be seen as a way of taking over this “author-building” function and performing it with greater flexibility.

Participants also waxed lyrical over cultural and artistic ambassadors for our work – leading authors, actors and public figures such as Stephen Fry, Ralph Fiennes, Helen Mirren and others who could be incentivized to endorse books, themes, authors, and Russian literature generally. Prizes also were discussed as a way of bringing recognition and prominence to works of Russian literature in translation. Founding and /or funding another “major” prize was suggested, though it seems that smaller awards or awards for smaller works “such as a poetry/short story prize” could be an effective place to start.

Another ambitious suggestion that found support among the group was to emulate London’s Pushkin House with an American venue (New York City would probably be the natural choice to host it – but also the priciest). Such a space, centrally located, could be a base for lectures, readings, and events relating to Russian culture – that is, not limited to literature. Indeed, the usefulness of such a space could be maximized and the cost brought down through partnership with other Russian-related cultural organizations, though the ultimate prize might be to find a respected donor willing to endow Read Russia with some Manhattan or Boston real estate.

On the other end of the scale in terms of cost outlay, many translators expressed interest in setting up an email discussion space (a listserv or Google group) as a way of keeping members of the Chatham group and other colleagues apprised of events in the Anglophone Russian literary world. For example, it could be a way of finding out when an important Russian writer or critic is being invited to the US and of coordinating additional North American stops that could increase visibility for little additional travel cost. (Though a mailing list would effectively cost nothing, it was not yet clear how it would best be administered or moderated.) Is there a social media platform for Russian literature – and if not, what would it be (Fetbook?). Also useful would be a project designed to canvas campuses and teachers to learn what books are most often assigned – and where opportunities might lie for more Russian literature. Finally, on the topic of authors’ visits, participants with experience in organizing book tours emphasized how useful it could be to have logistical support from Read Russia in arranging visas to bring Russian writers to the United States.

II. The Chatham Translation Symposium – 2021 and Beyond

Participants were pleased by the success of the scheduled discussions and informal conversations that took place in Chatham, and the guests greatly enjoyed the venue, activities, and company. Many participants specially noted the value of having both US- and UK-based guests presents, as well as the mix of younger translators alongside seasoned colleagues with many dozens of books under their belts.

Participants were pleased by the success of the scheduled discussions and informal conversations that took place in Chatham, and the guests greatly enjoyed the venue, activities, and company. Many participants specially noted the value of having both US- and UK-based guests presents, as well as the mix of younger translators alongside seasoned colleagues with many dozens of books under their belts.

For future iterations of the Symposium, it was suggested to maintain a focus on developing and discussing initiatives to increase the profile of Russian translation in Anglophone literary life – especially given that this is a topic not often emphasized in official discussions elsewhere, and one that squarely aligns with Read Russia’s overall mission. There were also various requests for more workshop activities, which might lead to a "finished product" that participants could each take home from the trip – and which takes advantage of the group's enviable collective skill level. Though we initially proposed that guests bring a “tricky passage” to work on with the group, we never ended up scheduling an activity or workshop to make use of this material. Another suggestion was to establish in advance a few areas of useful knowledge (e.g. historical trends) that could inform our discussions and that participants could do some preliminary research on in order to present findings to the group. Participants did, however, submit suggestions before the Symposium as to their favorite seaside or littoral passages in Russian literature – with one participant even performing his selection on the water (https://www.dropbox.com/s/evrhnw2l252n1ry/IMG_0836.MOV?dl=0).

A few participants suggested inviting more non-translators: more publishers/editors, perhaps specifically including publishers who don’t primarily focus on Russian materials; a guest or two who could speak to issues of reviewing – both how to get one’s own translations reviewed as well as the role that qualified translators have in reviewing each other’s works; and possibly even inviting one or more of the Russian authors whom we translate.

Although multiple participants noted that the scale of this year’s group was ideal, many suggestions of specific prospective guests were made. Suggestions for nominations are continuing.